IFS and Addictive Processes - including the ‘Rescue Team’

Over the past year we’ve been exploring Martha Sweezy’s Six Acts of the Shame Cycle within the Internal Family Systems (IFS) model. Today we’re focusing on the Rescue Team. I’ll weave together ideas from Cece Sykes, Martha Sweezy, and Dick Schwartz—and add a triangle to the cycle—to look at addictive processes.

Can IFS help with addiction and recovery? Absolutely. Below you’ll find IFS-informed suggestions for recovery—some may feel very different from what you’re used to. We’ll also touch on supporting someone with addiction the IFS way, including approaches to reducing or stopping substance use outside formal rehab settings.

If you’re new to IFS, here’s a short introduction:

https://www.stroudtherapy.com/internal-family-systems

About the video & meditation

In the video I reference a guided meditation by Cece Sykes: you’re invited to watch, as if on a TV screen, the part of you engaging in a soothing/comforting activity—while noticing another part that pushes back—and to sense the vulnerable parts underneath. I’ve included two meditations at the end of these notes: the Cece Sykes practice we used in the Drop-In, and another drawn from the book I mention throughout.

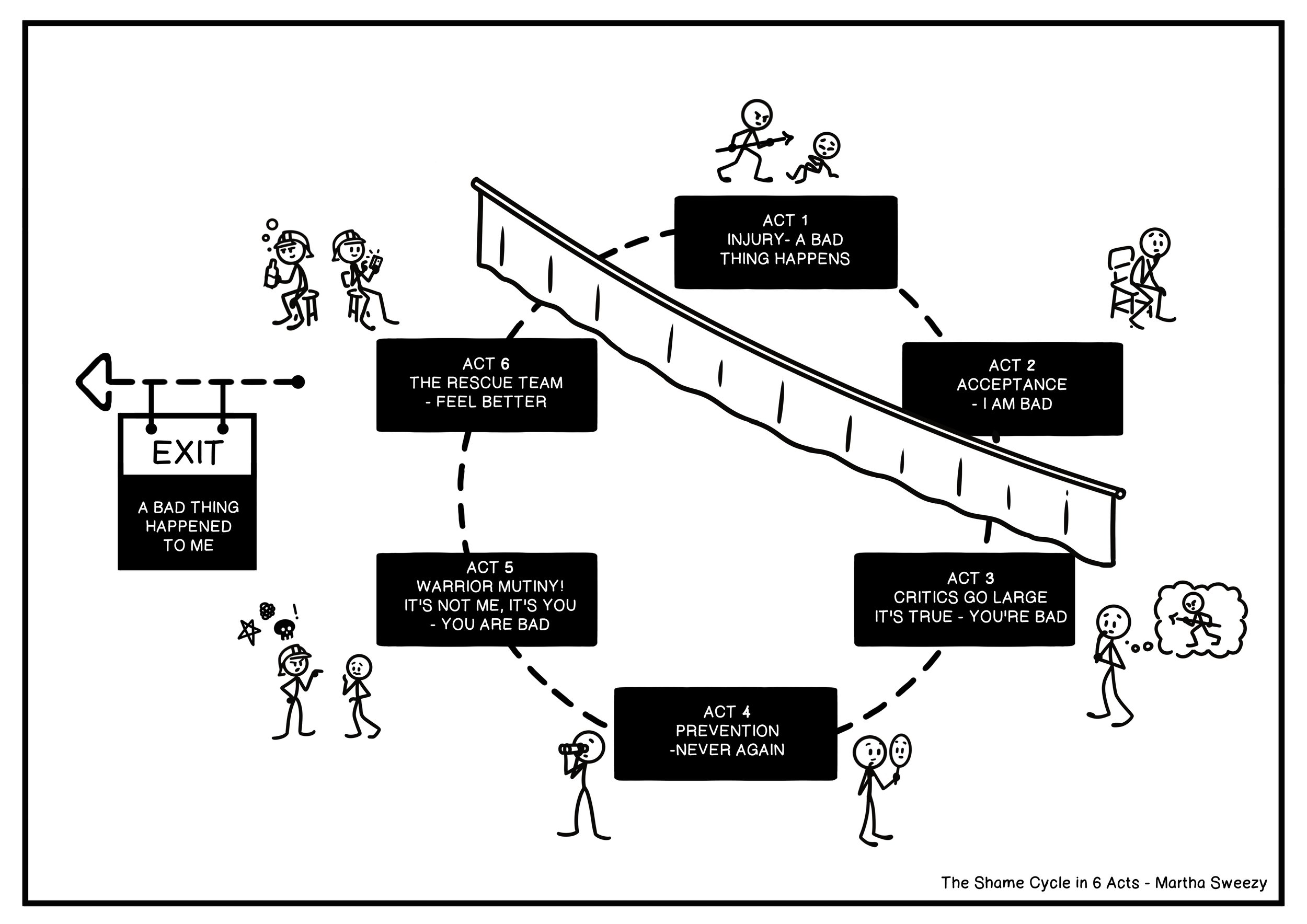

Recap: The Shame Cycle (IFS)

You’ll find Martha Sweezy’s shame cycle described in her book: https://marthasweezy.com/

I’ve also shared notes and videos on the other Acts in previous Drop-In talks (see the News section on my website). Christine Dixon of The Ordinary Sacred covers these—and much more—in her YouTube series as well.

The cycle runs as follows:

Something bad happens.

An authority figure shames you: “What’s wrong with you? You made me feel X.” This may be overt (words/actions) or covert (neglect; physical, verbal, or sexual abuse). The message lands that your natural emotions—joy, anger, exuberance—aren’t welcome. It’s not just your behaviour that’s “wrong”; you are wrong/bad.Acceptance.

The child believes it and takes on the burden as identity: “I’m worthless, unlovable, too much/too little, weak, even evil.” This is an adaptive move for a child—the world is good; I must be bad—but it leaves deep wounds.

— The curtain.

Many aren’t consciously aware of Acts 1–2; they predate current problems by years.

Acts 3–6 can appear in different orders and often polarise with one another. They’re the protective culmination of the wound:

3. Inner Critics go large (Manager).

Self-blame: “Something’s wrong with me—yes, I am bad.” The inner critic mimics the external shamer: “You’re so X…” It pushes suppression of exuberance, sexuality, anger, sadness, quietness, self-agency—“Shrink and you’ll be safe/loved.”

4. Anticipatory Scouts (Manager).

The “Never again” team. Eyes both out and in; reputation, hiding, doing it “right”. Afraid of criticism (from others and from internal managers). Determined never to let the system be vulnerable to that pain again; takes control to improve and protect.

5. Warrior Mutiny (Firefighter).

Distract and deflect shame by turning it outward: “You’re bad, not me.” Diminish others by comparison to reboot self-esteem; try to control the external world to keep exiles at bay. External, instrumental shaming—active, rebellious, often disinhibited. Intent is pro-social (to protect), effects are not.

6 Feel-good Rescue Team (Firefighters).

Soothing/numbing/pleasure at all costs: drinking too much, drug use, smoking, comfort eating, risk-taking—without regard for “side effects”. Internally they mean to help; interpersonally they’re asocial (they don’t factor others in), and the outcomes are often antisocial—strained relationships, unreliability, not showing up.

These Firefighters frequently end up in a massive tug-of-war with internal/external critics—and with other people’s Warrior Mutinies—while the most vulnerable parts remain unseen and unheard.

I’m now going to introduce the Addictive Processes framework. For a deeper dive, have a look at Cece Sykes: https://www.cecesykeslcsw.com/ and her talks on YouTube/Spotify/Apple.

Her book—co-authored with Martha Sweezy and Richard C. Schwartz—is excellent: compassionate, practical, and firmly grounded in IFS.

Her number 1 point is that we treat a system not a symptom Not to excuse but there’s always a reason for someone’s drinking/drugs etc

So here’s Cece’s triangle, which sits well alongside the shame cycle:

The triangle — Blame, Flame, Shame

Fragile, underlying exiles feel deficient, inadequate and abandoned for any number of reasons, past and present. They’re activated by external interactions or current challenges. (Shame cycle: Act 2.)

Managers try to ignore or contain these vulnerable parts by getting busy, focusing on tasks or others’ needs, staying in the head, or using criticism to goad the exile into “improving” and becoming acceptable. (Acts 3 & 4.)

Firefighters, noticing the exile’s distress and shame, take over and use substances or any number of practices (whatever it takes) to mask or medicate emotional pain. (Acts 5 & 6.)

Then:

Exiles feel sick, degraded, fearful and isolated — back to Act 2.

Managers mobilise again:

Task managers frantically try to get operations back on track to regain a sense of control and self-respect, and/or

Attitude/critical/moralising managers attack, vilify and shame the firefighters for their “transgressions”. (Acts 3 & 4.)

Firefighters (Act 6) then return to the addictive practice again — something, anything — to medicate the pain, block out the shame, and deny consequences. (Act 5: “It’s not my fault, it’s yours.”)

Which leads to:

Vulnerable exiles, unsought and unwanted, feeling abandoned again — reinforcing their sense of being hopeless and unlovable. The cycle continues ad infinitum.

What if we could do it differently?

The healing is in the relationship — both inside and out.

Addictive processes affect body, mind and spirit. When people engage in compulsive, repetitive use of substances or practices (gambling, porn, high-risk sex, over- or under-eating), it impacts physical health, reshapes the brain, and breeds despair. Intimate relationships suffer, families fracture, and communities fragment.

Cece Sykes, Martha Sweezy and many in the IFS community are inviting a paradigm shift.

Cece suggests you pause with the word “addict”. What stirs in you around that word? Which parts show up—memories of school, church, family; associations with criminality; or perhaps the raw emotional impact? Just notice.

She points out that mainstream treatment models have often leaned on confronting the “addict” and challenging “denial”.

In contrast, IFS proposes relational engagement with your inner system—healing attachment disruptions and earlier traumas that drive the addictive behaviours in the first place.

“But surely this will enable them…” say the sterner voices. “We need to keep the addict contained.”

Yes—12-Step helps many by providing relationships and community. For others, the rooms can feel controlling or punitive; it depends on the meeting.

Cece reminds us there’s now an IFS-informed 12-Step path, and of course psychotherapy—so it’s no longer so black-and-white.

In our culture there’s enormous stigma against people who use drugs.

The invitation is to work with our own systems: notice and do your U-turn. Meet the parts in us that get controlling, judgemental and critical—socially acceptable perhaps, but often deeply harmful.

From an IFS stance, compassion isn’t collusion: we can pair clear, Self-led boundaries and accountability with warmth and curiosity.

Cece’s focus isn’t on treating behaviours; it’s on treating what happened.

Most people with extreme systems carry high ACE scores—there’s trauma.

She invites us to picture a child amid a chaotic scene (parents drinking, the TV kicked). Two of many possible outcomes: in one, the child receives emotional nurturing; in the other, the child is ignored—no explanation, no comfort, no connection. Which parts then get that child to eat breakfast the next morning and go to school? Those protectors become hard-working: perfectionism, getting into fights, drinking—anything to cope and process. This doesn’t happen overnight. Some children start dieting at six to control something in their lives. Others hyper-focus on relationships. Many girls are socialised to be caretakers. Compulsive parts use strategies that worked for past emergencies but are costly now.

Cece invites us to see addictive processes as a chronic polarisation.

Think big picture—big teams: on one side, parts that put you first and help you escape; on the other, parts that comply, obey the rules, and keep you in line. “Attitude” managers often bring self-contempt and loathing; opposing them are parts saying, “I do this to turn off my brain.” Beneath both are exiles with healthy longings—to be loved and cherished—now burdened with shame, hurt and loneliness.

What am I supposed to do now?

What would it be like to sit with that young child who witnessed, was abused, abandoned, or exploited? Can we help?

Let’s look at our patterns. Using the shame cycle (or Cece’s triangle): I feel lonely → shame/dismissal → I’ll do better, be perfect, or pretend to be X → I feel even less seen → firefighters take me out. What if there’s a new way?

IFS is counter-intuitive. Instead of battling behaviour, we build a strong Self-to-part connection—the three-legged stool: Self, protectors, and exiles. We treat the whole system. We can’t just take away the firefighter—there’s always another waiting in the wings. We also need to befriend the critic.

As a therapist, I meet the managers who brought you to therapy. You want change—I support that vision. My goal isn’t to wrest control or make you different; it’s to help you build relationships with your parts. We work on regulation and attachment, and keep asking: How do you feel towards this part? I aim to know you and all your parts and to accept you as you are—a paradigm shift. You’re far more complex than any single behaviour. What did you need that you didn’t get—emotionally, physically? And if there’s a relapse, we’re not back at square one—more like square 30. Every part of the story gets a seat at the table. The goal is relationship, not control.

My job also includes honesty. I’ll speak for parts I notice: it’s disingenuous to say I’m “just here to help” while ignoring risk. I might say, “I’m noticing the stakes getting higher—parts of me are getting scared for you.” Change happens in a welcoming, regulated internal system, not under judgement.

Ask: What environment do I need to make a good choice? The “ninth C”—Choice—matters: how we frame options, pace the work, and present supports can make safer choices genuinely available.

So I normalise internal differences, highlight shared goals, and help you step between polarised parts so they can negotiate.

A quick note on neurodivergence: many of us use addictive processes as software firefighters—in response to masking, rejection sensitivity, or to medicate trauma. Monotropic hyperfocus can lock us onto a game, a person, fine wines—anything. Differences in dopamine/GABA and executive functioning shape impulse control and regulation. There’s excellent work here from Meg Martinez Dettamanti and Candice Christiansen, from advocate Viv Dawes, and Devon Price on addiction in autistic folk.

In the video I share that I’ve realised my mother was also neurodivergent, alongside having CPTSD from her own childhood, and how her overwhelm, obsession/hyperfocus, and rejection sensitivity contributed to extreme addictive processes that ultimately ended her life. I say, too, that at the end of her life I didn’t meet her with the compassion and relationship I wish I had. I’m working with that now—working to forgive myself.

What I want to name is that this is me speaking as an adult who’s spent years in therapy and 12-step rooms—and only recently, as a late-diagnosed/peer-reviewed AuDHDer, have I looked at my family with new eyes. I hadn’t understood that part of the puzzle of my upbringing was my family members’ neurodifferences as well as my parents’ trauma/CPTSD—specifically here, my mother’s neurology as well as her parts. I want to pass on the learning that, for a long time, my managers blended with me and blamed and shamed her for her extreme behaviours—behaviours that were firefighters responding to an overwhelmed nervous system as well as the usual parts dynamics.

To be absolutely clear: none of this implies that the injuries caused to my siblings and me—then or later—were acceptable. Nor is it an invitation to leap straight to compassion. We don’t spiritually bypass. In IFS terms, we don’t step over the hurt, upset, and anger that naturally arise when you’ve grown up with neglect or abuse of any kind. A great deal of therapy is grieving and tending to the burdens and identities we took on as children.

Finally… this is lifted from Cece, Martha and Dick’s book. I hope it’s useful.

Common behaviours of manager parts in addictive systems

Blaming critic: Attacks firefighters with hostility and contempt

Shaming judge: Labels firefighter behaviours as immoral or bad

Perfectionist: Terrified of mistakes; assumes there’s only one “right” way

Logical rationalist: Relies on facts alone; sidelines feelings

Intellectual: Talks about problems instead of taking action

Fixer: Assumes responsibility for other people’s actions or problems

Striver: Highly competitive; demanding of self and others

Rescuer: Prevents others from experiencing natural consequences

Caretaker: Excessive concern for others’ feelings

Over-giver: Generous to a fault; struggles with boundaries

Know-it-all: Must be right; wants things done their way

Controller: Polices firefighters (and anyone else) who doesn’t conform

Common manager characteristics in addictive systems

Responsible, compulsive workers who value being productive and “good” (often claiming, “This is the real me.”)

Care about appearances; work to seem legitimate, valuable and “normal”

Chronically anxious and vigilant; struggle to relax or trust Self, firefighters or exiles

Work overtime to prevent exiles/firefighters from taking over—often via hostility, shaming and blaming

Operate from the neck up; minimise or dismiss feelings

Common manager fears

Chaos and unpredictability when firefighters are in charge

A flood of shame and worthlessness after firefighter activity

That Self isn’t strong enough to help (or even doesn’t exist)

Exposure of secrets, old memories and painful wounds

That nothing will ever change

Common behaviours of firefighter (FF) parts in addictive systems

Alcohol use

Prescription/street drug use

Disordered eating (bingeing, purging, comfort-eating or restricting)

Sexual preoccupation, chronic fantasising, sexual risk-taking

Self-harm (cutting, head-banging, etc.)

Suicidal ideation or attempts

Gambling/overspending

Rage, violence, exploitation or abuse of others

Dissociation, tuning out, “getting lost”, reduced present-moment awareness

Fantasising about idealised success, power, or perfect relationships

Common firefighter characteristics

Chaotic, “out of control”, driven to keep using

Both impulsive (unthinking, unconcerned with consequences) and compulsive (no sense of choice)

Can soothe or distract in ways that are grossly overstimulating

Heroic: won’t back down; will “take a bullet” for the system

Narcissistic/self-absorbed in the sense that they prioritise the unmet needs of certain parts

Resistant to feedback; avoid noticing their impact; deny/minimise/hide use

Deeply committed; stay on the job until convinced exiles are safe enough

Common firefighter fears

That the hopelessness and despair of exiles will flood the system and cause a functional collapse

That managers’ shaming/inhibiting will become unbearable—and may evoke a suicidal part

That managers will over-accommodate other people

That therapists/managers/family/partners will control the client in harmful ways

Meditation we did in the Drop-In (from Cece)

Take a few breaths. If it helps, close your eyes. Let your parts know there’s no right or wrong way to do this, and they can ignore my voice if they wish.

Bring to mind one soother/distractor—a behaviour another part worries about (e.g., eating late, drinking, Netflix, shopping, scrolling, betting). Choose something manageable, not the hardest thing.

Imagine watching yourself on a TV screen engaging in it. Notice facial expression and body language: relaxed? stimulated? flat/tuned out? What happens in the body—ease, tension, activation, comfort?

Let this part know you’re witnessing it. Ask: How are you trying to help me? What do you want me to know? What are you afraid would happen if you could never do this again? Appreciate whatever it shares.

Now notice any push-back parts—the critics: “too much/too little/too late/too early/you should have this handled…” Let them know you see them. Ask: What are you afraid would happen if you didn’t come on so strong? If there were a safe way to help the soothing part use its energy differently, would that help you soften?

Gently notice any tender parts (exiles): shame, loneliness, not-good-enough. Let them know you’re here and available.

When you’re ready, draw a triangle. Jot down the firefighters you noticed, the managers weighing in, and any vulnerable parts underneath—plus their intentions and fears.

Meditation: what if the soothing activity were banished?

This exercise helps you notice which parts activate when a favourite behaviour is permanently removed (useful for understanding the fear many feel when told they must stop).

Get comfortable. Hand on heart and belly if you like; breathe into both centres.

Choose a genuinely enjoyable, non-controversial activity (e.g., walking in woods, reading, cooking). Watch yourself doing it. Notice body and face. Connect to the part who loves this.

Ask how important this is to the part. Then ask if it will play a short pretend game that may feel uncomfortable but will teach you something. If yes, announce the (imaginary) ban: this behaviour can never happen again. Be firm; don’t negotiate.

Notice reactions: body sensations, thoughts, feelings. If parts protest, imagine a shaming voice judging them for objecting—just to observe what happens inside.

Now reassure everyone: It was only an experiment; they can continue as usual. Notice the shift.

Take a few minutes to journal:

What did deprivation feel like to your system?

What was it like for parts to be told what to do with no recourse?

How did it feel to be judged for objecting?

How might this inform how you connect with a client (or yourself) around an addictive process?

Credit: the concept originated with IFS Senior Trainer Mary Kruger.