A brief introduction to IFS and Shame: the Shame Cycle in 6 Acts

This material is drawn mainly from the excellent new book by Martha Sweezy — Internal Family Systems Therapy for Shame and Guilt (see image below). I’ve doodled some stick figures to help me visualise the concepts—hope they’re helpful for you too.

This talk touches on only a small part of Martha’s book; I highly recommend reading it, or watching Christine Dixon (Ordinary Sacred), who walks through much of the material in a clear video series: https://www.youtube.com/@theordinarysacred6664

The talk formed part of our Stroud IFS-informed Drop-In in September 2023. For details, see the Drop-In page on my website: https://www.stroudtherapy.com/monthly-drop-in

Firstly… thank you for being here.

“Shame” comes from a Scandinavian root meaning “to hide” — and yet here we are. IFS and multiplicity make this work more approachable and as safe as possible. My hope is that it becomes clear: every part of you makes sense.

If strong feelings arise as you read or listen, try sending warm attention to those places. Invite any critical parts to give you a minute; ask distracting parts to soften. A hand on the area can help. It may feel overwhelming, and the more we understand the shame cycle, the more we can spot it and unblend. There is a beam of light through this — we can understand it, and we can help.

What is shame (in IFS terms)?

Shame = a global identity belief — I am bad, unlovable, evil, too much, not enough…

Guilt = my behaviour wasn’t OK — which points to repair: How can I mend the rupture?

Some people “accept the belief” that they’re worthless at their core; it becomes an identity. Martha Sweezy and the IFS community see this as a burden — something done to you. A part carries an experience of shamefulness, and other parts protect you from that awful feeling in whatever way they can. We all have inhibitory managers and disinhibited firefighters; that doesn’t make anyone a bad person.

Does shaming ever help?

Sweezy (and many others) finds that shaming individuals backfires — often spectacularly. It’s psychologically painful and quickly becomes self-generating: self-loathing, fear, inner/outer berating, addiction, making ourselves smaller, locking away traits and parts. What if there’s another way?

We live in authoritarian cultures where shaming is sanctioned — by teachers, parents, siblings, institutions. Intentions may be “to keep people on the right path” or serve as a social mechanism to maintain order. However, it’s magical thinking to assume my intent dictates your experience. Only my behaviour lands in your system — and when shamed, most of us simply feel hurt.

Guilt is prosocial and reparable. We want appropriate guilt: it helps us repair and stay in relationship.

Shame is not useful for individuals (even if groups sometimes use it to enforce norms).

Always check the guilt: is there an actual transgression? If not, imposed guilt is maladaptive — it harms the person and the relationship. (e.g. “You should do X for me” — pause: am I responsible for this adult?)

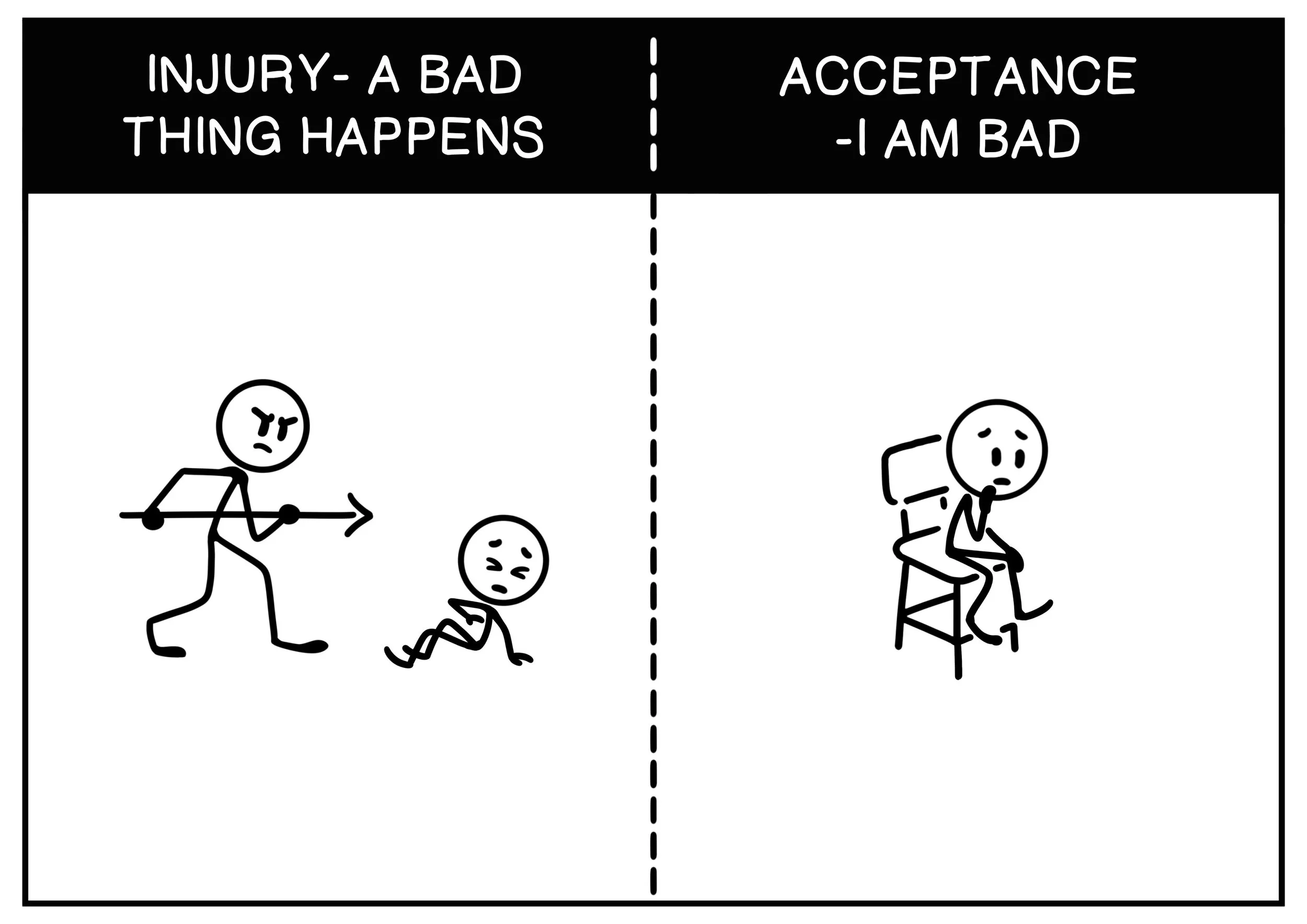

The Six Acts of the Shame Cycle

1) Something bad happens.

An authority figure shames you: “What’s wrong with you? You made me feel X.” The child is passive in this interpersonal moment. It might also be neglect or abuse (physical, verbal, sexual). The message received: your exuberance, joy, anger are not welcome. It’s not just behaviour that’s wrong — YOU are wrong.

2) Acceptance.

“I am bad.” The child believes it and takes in the burden as identity: worthless, unlovable, a mistake, too much, too little, evil, weak. It is adaptive for a child to internalise badness — it preserves the belief that the world (and carers) are safe and good; I must be the problem.

The Curtain

For some people there’s a “curtain”: they’re not even aware this is happening. It can predate current problems by years, so they’re unaware of the issues playing out now.

Acts 3–6 can appear in different orders and often polarise with each other. They are the culmination of the wound—parts mobilise to protect the child.

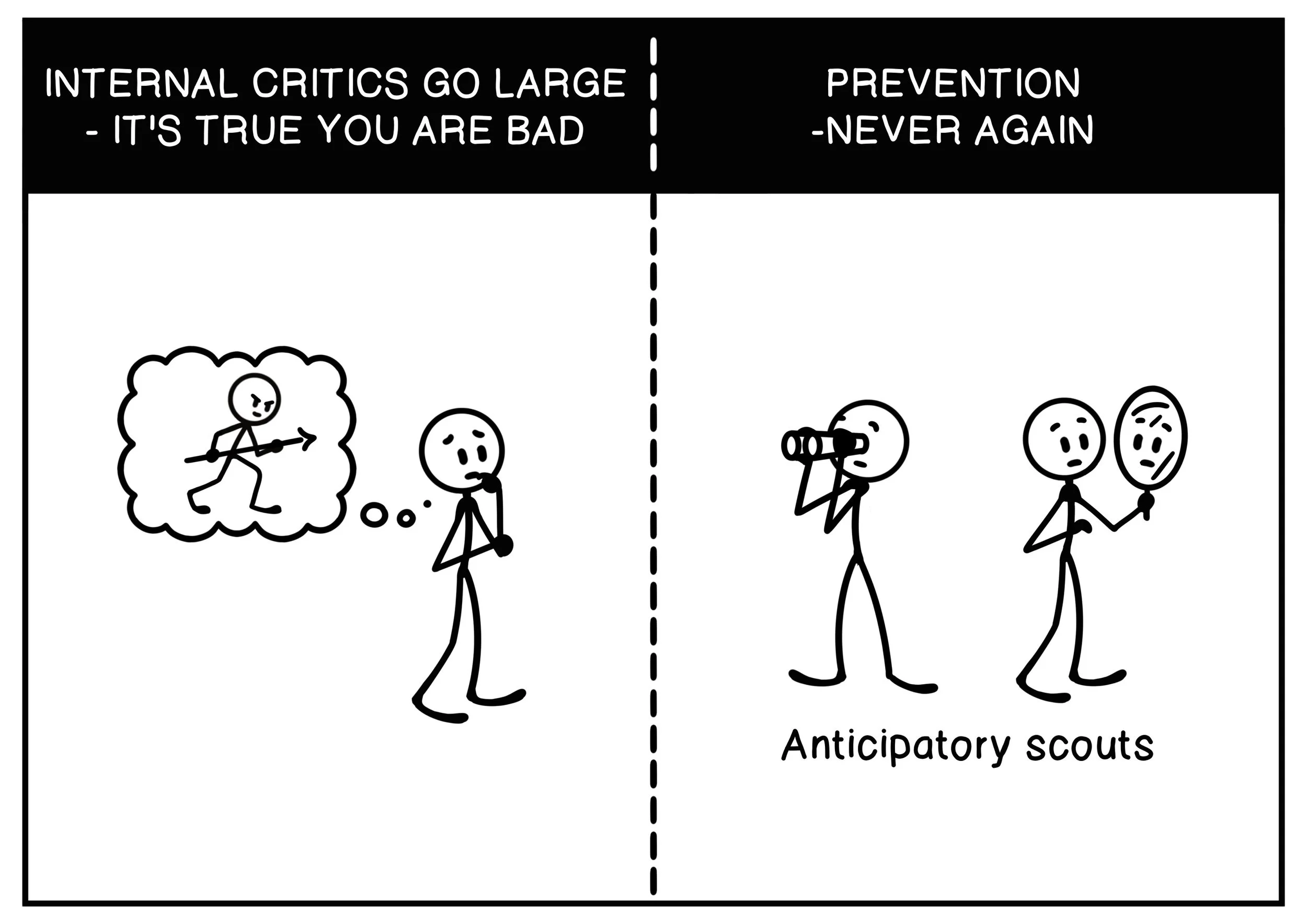

3) The Inner Critics Go Large (Proactive Manager)

Self-blame: “Something’s wrong with me. It’s true—I’m bad.”

Internal shamer mimics the external one: “You’re so X… you’re unlovable.”

Core fear: the child is held responsible; critics aim to “improve” the child—act differently or lie low.

Targets exuberance, sexuality, anger, sadness, quietness, self-agency.

Message: “If you suppress yourself and make yourself smaller, you’ll belong and be loved.”

This is instrumental shaming: a pro-social intent (safety, belonging) with hurtful effects.

The system now holds two parts locked in: the shamer and the shamed.

4) The Anticipatory Scouts (“Never Again”) — Manager

Motto: “Never again.”

Reputation management: hide, get it right, watch for danger. Eyes turned outwards and inwards.

Afraid of criticism from others and from internal managers.

Vow to prevent the system from ever being that vulnerable again; attempts to improve and control.

Survival via belonging: pro-social intent, diligent vigilance—yet the effects are not good.

Keeps everything locked up, keeps us hiding (and can drive anti-social withdrawal or Firefighter backlash).

As one Scout might say: “The hologram is safer than the whole of me.”

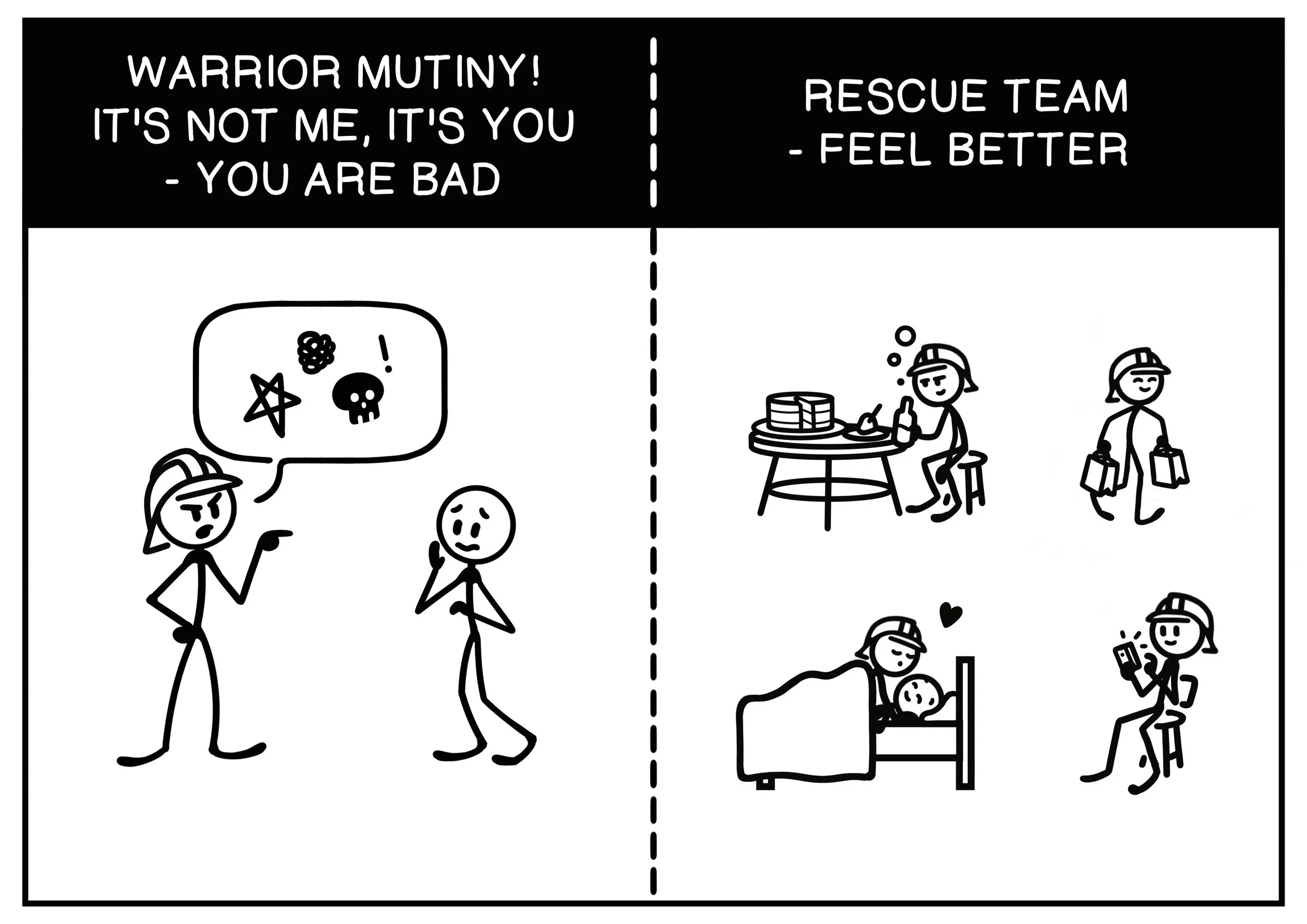

5) The Warrior Mutiny — Firefighters

Firefighters distract and deflect from shame by turning the focus outwards.

Projection: “You’re bad — not me.” Diminishing others by comparison to reboot self-esteem.

Control the external to keep Exiles at bay; pushing painful shame out onto others feels easier to manage.

This is external, instrumental shaming: active, rebellious, disinhibited in effect, while the intent is still (paradoxically) pro-social — to protect the system.

6) The Feel-Good Rescue Team — Firefighters

Aimed at making you feel better now through soothing, numbing, and pleasure.

Routes include drink, fantasy, sex, shopping, scrolling, etc.

Often risk-taking and unconcerned with outcomes in the moment.

Can be asocial externally: strained relationships, not showing up, unreliability.

Frequently locked in a tug-of-war with internal and external critics — and with other people’s Warrior Mutinies.

There is an exit

We each have an innate antidote to shame and burdened parts: connection with Self. With compassion for protective parts—really loving them up—we can then witness and re-parent the hurt child who carries the burden, and let that burden go.

People usually come to therapy struggling with one or more of Acts 3–6. We help them befriend parts and learn their good intentions; in time, Acts 1 and 2 emerge—often last, because they’re so vulnerable and painful. This is the root of why everyone is working so hard.

What’s distinct about IFS?

It treats the mind as an interactive system of parts. We facilitate relationships inside: How do you feel towards this part? And that one? Many therapies recognise multiplicity; IFS offers a clear, experiential way to access, relate to, and have compassion for parts.

Bottom line: the answer is compassion. There is an exit from suffering, and it’s built into all of us.

When you’re hurting: the “oxygen mask” move (after Martha Sweezy)

Something happens between you and another person; shame surges. You notice you’re hurt.

Name it: Ouch—that hurt.

Breathe: take a few slow breaths.

Protect the vulnerable one first: before inner/outer shamers pile in—or before a part reaches for drink/scrolling/escape—notice the impulse to react.

Turn inward: Hi, I see you. To the protectors: It’s OK. Relax for a moment. I’m here. We don’t have to deal with this right now.

Create space: I need a minute to look after the part that’s hurting. When they feel steadier, we’ll decide how to respond.

Invite a tiny experiment: Let’s unblend a little. Find the exile, offer care and witnessing, re-parent, and—when ready—redo and unburden.

Compassion leads.

If you’ve transgressed and caused hurt (repair beats apology)

Perhaps a Warrior-Mutiny moment ruptured things with your child, partner, or friend. Becky Kennedy’s excellent TED talk is a great primer: https://www.ted.com/talks/becky_kennedy_the_single_most_important_parenting_strategy

Key ideas:

It’s never too late. Get good at repair.

Go back to the moment of disconnection, own your behaviour, and name the impact.

Repair ≠ apology. Apologies can shut things down; repair opens a conversation, assumes a rupture, and builds safety.

Reframe identity and behaviour: I’m a good person who had a hard moment. Use your energy to repair and decide what you’ll do differently next time.

Name what happened, take responsibility, state the new plan. This averts the lifelong story of blame and restores safety and connection.

Alternatives to shaming

Self-led, conscious approaches (see Becky Kennedy’s book), and Nonviolent Communication.

Not only more respectful—they work better for healthy people and relationships.

Ask rather than demand. Be curious. Allow a part to move through naturally.

Lead with compassion, calm, and playfulness. That’s where change takes root—and where the magic often happens.